Written on the Walls

The Civil War Graffiti in the

Historic Frederick County Courthouse

This tour was made possible through the generous support of

Tom and Lesley Mack

Leaving a Trace

Civil War Graffiti

Civil War soldiers would commonly leave graffiti – signatures, inscriptions, and drawings – wherever they went, but this was especially true when men were prisoners. During the war this courthouse was frequently used to temporarily hold prisoners. The evidence of repeated imprisonments covers the walls. Often, these men left not only their names but also their regiment and in some cases the date and place of their capture. Some may have hoped that, by leaving some trace, friends and family might be able to discover what happened to them – in case they did not make it home. Other times men were simply drawing on the wall to pass the time, or even writing to express deep frustration. Much like letters and journals, graffiti like what you see here offers us a direct window into the lives of these soldiers. Until the year 2000, when the courthouse was first renovated for museum use, the graffiti had been hidden behind paneling and its rich stories were unknown.

Graffiti #1:

The Yankee Doodle

This graffiti is located on the first floor of the museum, in the back left corner. This doodle likely depicts a Northern soldier in a demeaning way. The soldier appears to be depicted as a horse or mule wearing women’s clothing. Notice that the figure is holding a rifle straight up with the bayonet fixed. This indicates that the graffiti artist might have been drawing a guard who was standing outside this window. The word next to the doodle appears to be “Yank” so it is likely that this was drawn by a Confederate soldier.

Artist James Taylor sketched the scene in front of the courthouse following the Third Battle of Winchester.

Multiple accounts estimate that 1,000 Confederate prisoners were held here at the courthouse at this time.

These prisoners were then moved to Union prisons such as Point Lookout and Ft. Delaware

Graffiti #2

1st Lt. John E. Wills

This graffiti is located near the floor at the top of the stairs outside the exhibit hall (behind the quilt). Pictured here later in life, Confederate Lt. John Wills was 38 years old when he was captured at the Third Battle of Winchester (September 19, 1864) and held prisoner here at the courthouse. While here, he wrote his name and unit on the courthouse wall. Wills was held at the courthouse for nine days with seventy-three of his comrades. James E. Taylor, a “special artist” for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, sketched a group of these prisoners in front of the courthouse. Will’s regiment, the 51st Virginia, had 5 killed, 55 wounded, and 74 captured at Third Winchester. The 51st fought in many other battles, including Fort Donaldson, Chancellorsville, Knoxville, New Market, Cold Harbor, Second Kernstown, and Monocacy. From here, Wills was transferred to Fort Delaware, where he endured a cold winter at the old fort that was being used as a prison. Wills and his fellow prisoners were sent home two months after the war ended. Almost fifty years later and suffering from “the infirmities of old age,” he applied for a pension in the town where his military career began. Wills had married Matilda Novell in 1856. After the war, he went back home to her and his four children in Elon, Virginia. Four more children were born after his return. He died in 1912 and is buried with his wife in Elon.

Graffiti #3

The Jeff Davis Curse

Nobody knows who left these scathing words damning Confederate President Jefferson Davis. However, it is a testament to the degree of anger and animosity held by Civil War soldiers. Whether Union or Confederate, this soldier went to great lengths to chisel each letter into the wall, which is why it remains so clearly visible. This stands as one of the most unique and significant pieces of Civil War graffiti that exists today. While we don’t know his name, the voice of this soldier still speaks to us through these chilling words:

“To Jeff Davis

May he be set afloat on a boat without compass or rudder

Then that any contents be swallowed by a shark

The shark by a whale, the whale in the devil’s belly

The devil in hell, the gates locked, the key lost

And further, may he be put in the northwest corner with a southeast wind

Blowing ashes in his eyes for all ETERNITY”

Graffiti #4

Corporal Albert B. Robinson

Captured in Loudoun County, Virginia, on July 20, 1863, Albert Robinson was held briefly at the courthouse before being sent to Richmond, Virginia. Then-Private Albert Robinson was still a raw recruit when he was wounded and was captured at the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas), the Civil War’s first major battle. The 19-year-old farmer survived the next 10 months in prisons as far away as New Orleans. Finally paroled in North Carolina but sick, he rejoined his now veteran regiment in late September, 1862, serving as a camp policeman and bugler. The next year, Robinson was with the 2nd New Hampshire when the Confederates unleashed a furious assault at the Battle of Gettysburg. 56 New Hampshire men died that day. Robinson escaped unhurt but his luck again ran out two weeks later. Sick and unable to keep up with his unit, he was captured by retreating Confederates and sent to Richmond via the Winchester Courthouse. His fortunes soon improved. He was paroled and rejoined the 2nd New Hampshire, then guarding southern prisoners at Point Lookout, Maryland. As his eventful three-year army career ended, now Corporal Robinson survived the Battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia. After the war, he migrated to El Paso, Texas

Graffiti #5

Union Private William H. Selah

William Henry Selah enlisted in 1861 from Marshall County, Virginia (modern day West Virginia). At the outbreak of the Civil War, Marshall County was in the northern panhandle of the state and was bordered by Ohio and Pennsylvania. That area strongly supported the North, and 17-year-old Selah joined to fight as a pro-Union Virginian. While the majority of Virginians fought for the Confederacy, many of the western counties decided to stay loyal to the Union. Private Selah fought against fellow Virginians at the Battle of McDowell on May 8, 1862, Stonewall Jackson’s first victory of his Valley Campaign. Almost a year later, the citizens of the fifty counties voted to make West Virginia the 35th state of the Union. Private Selah may have been captured and either released or escaped after the Battle of Gettysburg, or he may have passed through Winchester in 1864. He was part of the 3rd Virginia Mounted Infantry, Co. I, from July to December 1863. He then served from January to August 1864, in the 6th West Virginia Cavalry, Co. I. Selah stayed with the same unit, although its name changed, throughout his three-year enlistment.

Graffiti #6

Confederate Private Henry Kissel

Confederate Private Henry Kissel served in the 5th Virginia Cavalry. The 5th Virginia Cavalry was on the sidelines or barely involved in the battles of Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. The regiment saw action in the Virginia battles of Malvern Hill, Aldie, and Brandy Station. Kissel enlisted on June 5, 1861, in Petersburg, Virginia. According to what he wrote on the wall, he was the company bugler. He deserted sometime in November or December 1863. Another deserter from the 5th Virginia turned himself over to Union forces at Dumfries, Virginia, on March 29, 1863. He explained why he quit: “no pay, no clothing, and only one-fourth pound of meat a day.” Was Kissel similarly disillusioned, seriously ill, or going home to a needy family? It is a mystery since no other record has been located that positively links this soldier to any post-war activity or location. He could have died or changed his name.

Graffiti #7

Gettysburg Officers

Here you will see the names of more than a half a dozen Union officers that were held prisoner here during the Gettysburg campaign in July of 1863. After their defeat at Gettysburg, Confederate forces were retreating back into Virginia via the Shenandoah Valley. Union forces, mostly cavalry, pursued the Confederates. Some of these Union soldiers were captured and held here in this courthouse before being marched to Staunton and then taken by train to Richmond.

Graffiti #8

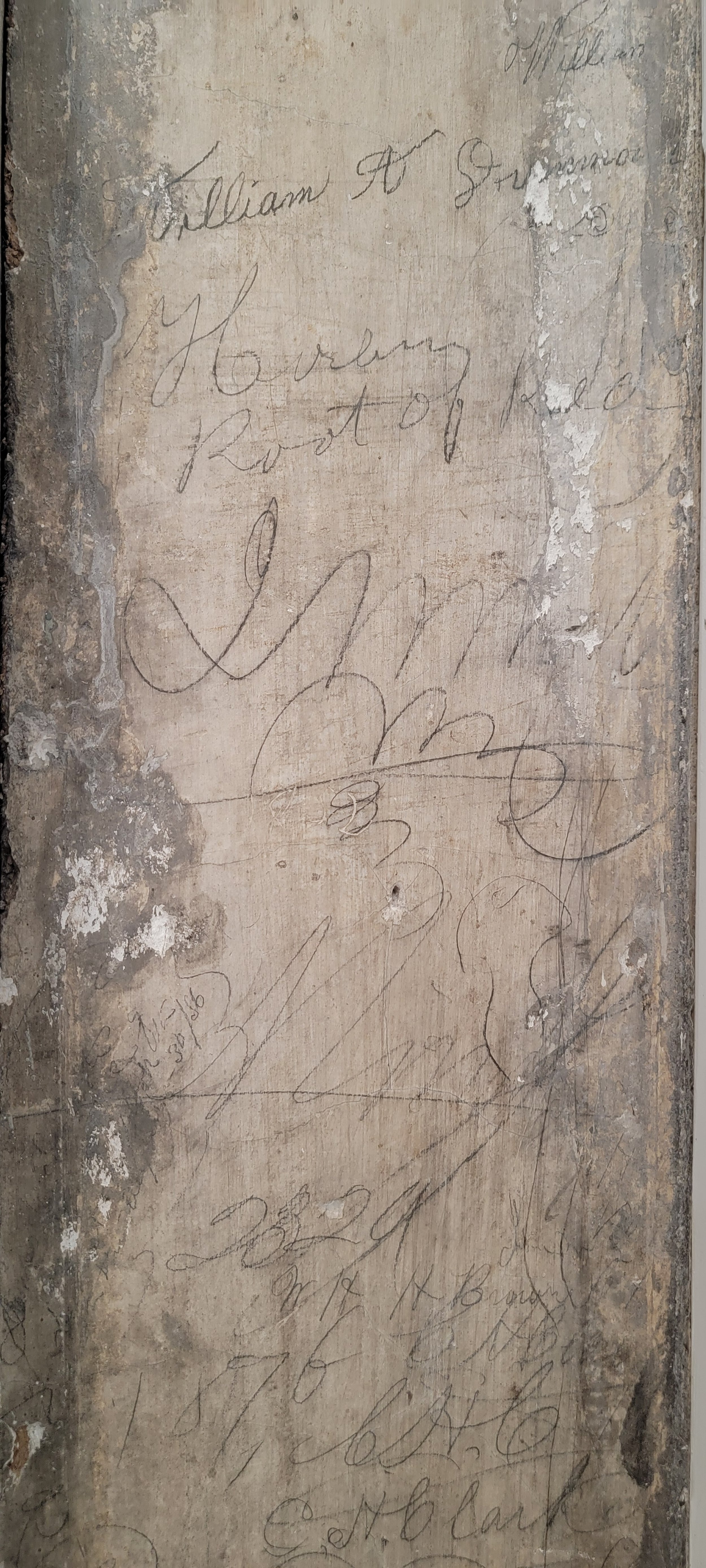

Miscellaneous Graffiti

This section of the wall is an excellent example of the variety of graffiti that was written and inscribed on these walls during the Civil War, with drawings, signatures, military units, and hometowns – for instance, “Philadelphia, PA” can clearly be seen.

Graffiti #9

Henry A. Jones

Raised in the Union Capital during the exciting war years, fifteen-year-old Henry Powell changed his name to “Henry A. Jones” and lied about his age in order to join the army. The graffiti that Henry A. Jones left behind on the wall is bold and clear, but his military career is a puzzle. Jones enlisted at the age of 15 on October 10, 1865, months after the Civil War ended. He joined Company F, 5th U.S. Cavalry, a unit that was assigned to the District of Columbia after the war, probably providing provost duty. Jones was a trooper in a provost guard stationed in Winchester from May-August, 1866. He was arrested for desertion three months after enlisting and was confined for a month. His record also shows that he had many illnesses and was in the hospital various times in 1865 and 1866. He could have been here in the courthouse serving as part of the Provost Guard, serving time for desertion, or recovering from one of his illnesses. His recent schooling is evident in his careful signature, inside ruled lines, on the wall of this room. The 5th went on to Richmond and Powell was discharged in 1868 after his horse “fell while on drill...and mashed in my side”. Jones left the Army in April 1869 and died in Maryland in 1888 of alcoholism. When his widow filed for a war pension after his death, she revealed that Henry A. Jones was really Henry A. Powell. There was no explanation why Powell enlisted under an alias. The War Department rejected the claims. Powell’s story reminds us that each side had soldiers who were anything but heroic and were quickly forgotten. However, the simple act of writing his name on the courthouse wall has assured that his mysteries have a place in history.

Graffiti #10

The Farnsworth Doodle

Here we can see the doodle of a man falling from a horse. Broken plaster obscures the image, but we can see a leg in the air and a figure that appears to be holding a sword. We believe that this graffiti was left by Major Charles Farnsworth, one of the Union officers captured and held here during Lee’s retreat from Gettysburg. During a skirmish near Halltown, West Virginia, Farnsworth was shot off of his horse and then fought hand-to-hand with his saber before he was captured.

Graffiti #11

Union Private John Richards

Captured in Loudoun County, Virginia, on July 20, 1863, Union Private John Richards was held briefly in the courthouse before being transferred to Belle Isle Prison in Richmond, Virginia. Richards, the 21-year-old blacksmith son of farmers, answered President Lincoln’s call to arms after the firing on Fort Sumter, South Carolina. During his first year with the 16th Massachusetts Infantry, spent at Fort Monroe, Virginia, he witnessed the history making battle between the iron ships Monitor and Merrimac. In August of 1862, Richards was swept up as a Confederate prisoner during the Battle of Second Manassas. Paroled and returned to his regiment in December, he still owed $12.00, more than a month of his salary, for “extras” to the regimental sutler. After surviving Gettysburg, Private Richards fell sick and became a straggler. Retreating Confederates again made him a prisoner of war. After being briefly held here in the courthouse, he was transferred to Belle Isle in Richmond, where he spent a sweltering, disease-ridden summer. By October he died of pneumonia, a forgotten statistic in a southern hospital. His comrades in arms, who listed him as a deserter, recorded his death during a prisoner exchange.

Graffiti #12

Union Private David Powell

20-year-old Union Private David Powell was captured on July 24, 1864, at the Second Battle of Kernstown and held at the courthouse in Winchester for several days. A peddler by trade, Powell first served as a volunteer from October 11, 1861, to February 10, 1864. He reenlisted in 1864 and was received a fifty dollar bounty. Powell’s first three years had been uneventful, guarding trains in West Virginia. His war career took a dramatic turn when the 54th Pennsylvania joined the fierce f ighting in the Shenandoah Valley 1864. After surviving months of hard marches, ferocious battles, and a slight wound, he found himself dodging bullets behind a stone wall in Kernstown on the morning of July 24, 1864. Under a Confederate onslaught, the Union line collapsed, and Powell was gathered up by the enemy and herded to this courthouse with scores of his comrades. Listed as missing in action on his regiment’s roster, Powell had his first taste of what a prisoner faced right in this room. Local resident Mary Greenhow Lee was concerned about suffering soldiers, blue or gray. Her diary entry of July 27, 1864, recorded that “...the Yankee prisoners have had nothing to eat for several days; it made me miserable to think of the creatures being starved… but today they had rations and tomorrow will have full ones” Spared the worst horrors of prisons like Andersonville, the five foot five, dark-haired private was transferred to Danville, Virginia, and survived a fall and winter of imprisonment. Ironically, his entire regiment, the 54th Pennsylvania, was captured by General Lee’s army only days before the Confederate surrender on April 9, 1865. Freed after the rebel defeat, Private Powell ended his military career at Camp Parole, Annapolis, Maryland, returning home with $49.01 of back pay in his pocket.