Help Save Manor’s Hill at New Market

This c. 1920 image was taken from Shirley’s Hill. The height in the near distance is Manor’s Hill. The target property is in the center of that height. Image courtesy VMI Archives.

We’ve been working to save the Manor’s Hill parcel on the New Market battlefield for quite a while, and now, thanks to an amazingly generous donation of value by the property owner, victory is within reach. I’m writing to ask you to make a contribution that will help us raise the $130,000 needed to get this done.

Preserving this 5-acre parcel of core battlefield will protect the site for all time and open more than 175 acres of the New Market battlefield to the public. This is because the property in question is almost surrounded by battlefield lands that you have already preserved, and has the amenities needed to make the site a ready-made trailhead and visitor contact station. But without the needed road access, parking facilities, and proximity to a viable trail route, there has been no way to get all of these preserved lands open to the public; almost 30% of all the lands preserved at New Market by the Battlefields Foundation and its partners have been inaccessible. You can change that. With your contribution we can save this ground and we can begin working with our partners to reimagine the battlefield experience at New Market, the “biggest little battle of the war.”

The math on this deal is pretty amazing. To preserve this property, we only have to raise $130,000 – $100,000 of those funds are needed for the purchase, and $30,000 is needed to pay for the due diligence costs (legal fees, closing costs, appraisal, survey, etc.). What makes this so amazing is that the property is valued at $3 million!

About half of that value is in the property’s improvements. The current owners constructed a museum and visitor facility on a corner of the site in 1989 and have operated a military museum there ever since. The museum contains one man’s private collection with exhibits featuring artifacts from the ancient world through the wars of the 20th century.

Although we are purchasing the entire property, including the museum building, you and I only have to pay for the ground. That’s because the owners have agreed to donate $1.5 million of the property’s value!

Not only that, they’ve also agreed to give you and I the time that we need to raise the remaining funds to complete the purchase. We are working with the Commonwealth of Virginia to partner with us in protecting this property and are applying to the American Battlefield Protection Program for the remaining $1.4 million that will be necessary to complete the purchase. But none of that can happen if you and I don’t pull together the $130,000 needed to get this project off the starting line.

What I’m saying is every dollar you contribute will be multiplied more than 21 times in its preservation power! When this deal comes together, the $130,000 that you and I have raised will be matched 21:1. Your $100 gift will have the buying power of $2,100 in this deal! There is no active preservation project in the country that I know of that will give you this kind of return – leveraging your money by more than 21:1 to save core battlefield.

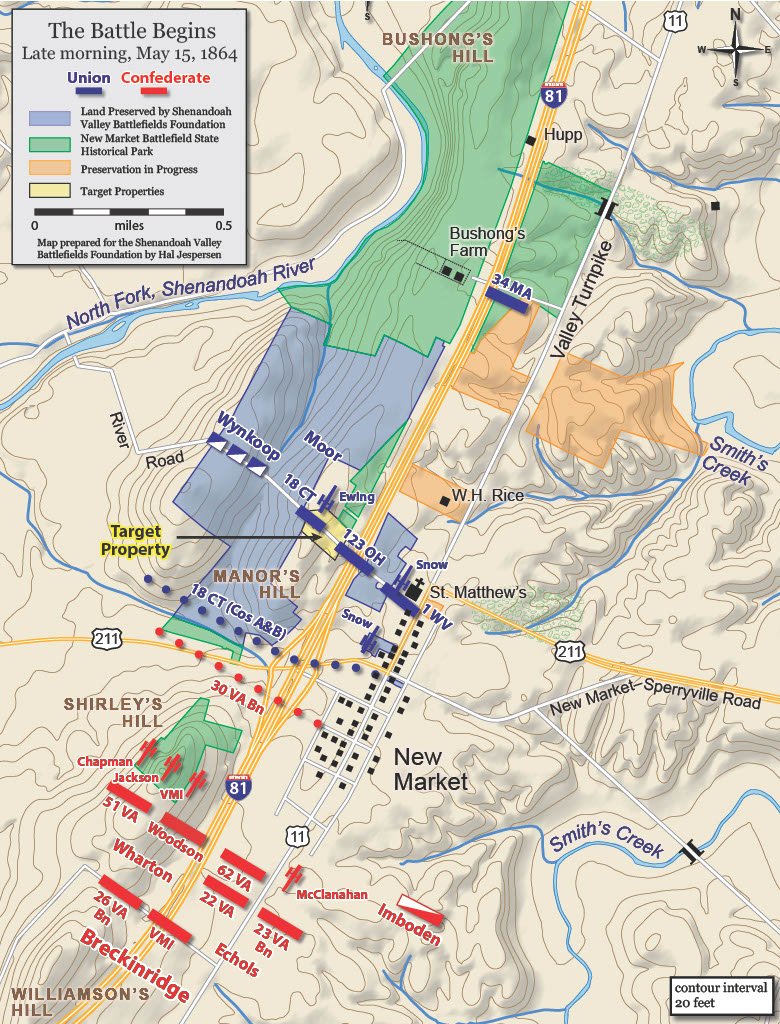

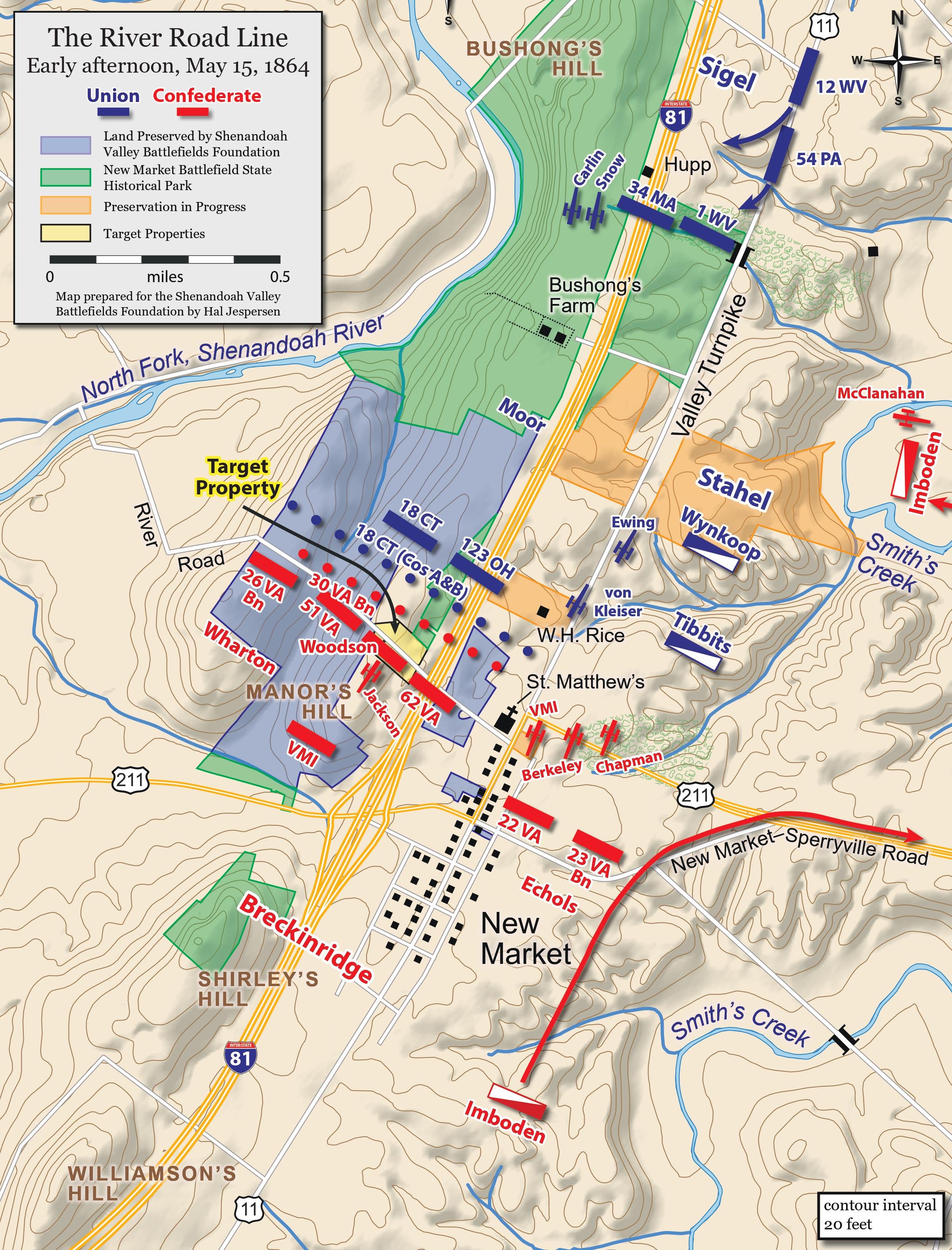

Take a look at the two maps that Hal Jespersen and Terry Heder have put together for you, each map showing a phase of the battle. This property was heavily involved in the fighting in and around New Market for two days. During the running fight between cavalry forces on May 14, 1864, the day before the main battle, Confederate Gen. John Imboden’s troops held this hill before falling back to Shirley’s Hill and then Williamson’s beyond. The pursuing Federal troopers swept across this property, driving the Confederate horseman in front them before falling back that evening to take up a defensive position on these heights.

The old River Road that ran from the Valley Turnpike in the heart of the town of New Market westward to the Shenandoah River runs through the middle of this property. It was along this road that Union Col. Augustus Moor established the first Union battle line of the coming engagement as he brought up his infantry troops to join the cavalry already in place. The road where he set his line is still plainly visible across the property and, when we complete this project, will be used as a walking interpretive trail with people being able to park on the target property and follow the old River Road deeper into the battlefield and then on through more than 170 acres of pristine battleground.

As Moor deployed his approximately 2,300 Federals, his artillery arrived and went into position on the target property. Ewing’s West Virginia gunners unlimbered their pieces and began firing shell after shell toward the Confederates on the hill to their south. That night, May 14-15, the night before the Battle of New Market, Imboden’s Confederates crept forward through a constant rain and made several sharp attacks along the Federal position, with the Federal defenders sending men forward to counter the Confederate effort. This property was in the thick of the fight, making it one of the rare locations in the entire war where intentional attacks were launched after nightfall.

On the morning of the battle, May 15, 1864, an artillery duel lasting hours erupted between the two armies with the guns on the target property belching shot, shell, smoke, and flame into the driving rain. Skirmishers of the 18th Connecticut moved forward out of the River Road to spar with skirmishers of the 30th Virginia who had been thrown forward in advance of the Confederate assault. The fighting was sharp and was followed by a Confederate attack all along the line with Wharton’s brigade charging Manor’s Hill.

By 2 o’clock, Moor’s men had been driven out of the River Road and the Confederates held Manor’s Hill, the River Road, and the Town of New Market. Jackson’s battery of Confederate gunners was brought up the heights and positioned on the target property, and fired into the Federals as they attempted to form in their second position. Soon the fighting would move north, and the action at Manor’s Hill would come to a close.

Manor’s Hill is an iconic part of the New Market battlefield, essential to understanding the battle. And this project is essential for the future of the battlefield. Preserving the Manor’s Hill site will prevent further commercial development; creating a new trailhead and visitor experience on the property will open up large new parcels of battleground to the visiting public; and completing the project will help fulfill our vision to tie together all the properties preserved in New Market into one engaging battlefield experience. We’ll multiply every dollar you send 21 times! So come on, let’s take the hill… Manor’s Hill… it will be hard to do it without you.

See you at the front,

Keven Walker

To donate, fill out the form at the bottom of this page or click here

Manor’s Hill at New Market

“A Cold Chill Runs Down Our Backs”

The Road to New Market

In the Spring of 1864, as a part of his coordinated offensive against Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army, Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant ordered Gen. Franz Sigel to advance south in the Shenandoah Valley.

Sigel’s opponent, Confederate Gen. John C. Breckinridge, hurried to concentrate his available forces – including the VMI Corps of Cadets – to block the Federal advance. The two forces would meet at the small crossroads hamlet of New Market.

Early Fighting and Nighttime Clashes: “[We] fired into their faces”

Col. Augustus Moor commanded the Union troops that manned Manor’s Hill. Image from Scott Patchan private collection.

On May 14, 1864, advance elements of Sigel’s force moved south on the Valley Pike towards New Market and clashed with Confederate cavalry, gradually pushing the southerners through town. By day’s end, the Confederate line was south of town. The opposing Union forces, commanded on the field by Col. Augustus Moor, were positioned on the Manor’s Hill/River Road line. Union Pvt. Leander Cole of the 123rd Ohio recalled how, “[we] laid on our arms all night. Were in a cold rain here skirmishing with some heavy firing every few minutes.”

The firing Cole mentioned were harassing attacks that the Confederates launched at the Manor’s Hill line in the dark of the night. Confederate Jasper Harris of the 62nd Virginia described how, “[We] sneaked up close to their lines and fired into their faces.” And a Union soldier of the 1st West Virginia recalled that “They came until within sixty yards of our front…such a fire was poured out from our muskets was irresistible.” Another West Virginian said, “After considerable firing in the dark… the enemy in line” advanced, but the regiment “delivered a steady, well-sustained, and… destructive fire, driving the enemy’s line back from the entire front.” It was an exhausting, cold, wet, hunger-filled night for the Federals on the Manor’s Hill line. Union soldier Joseph Winter summed up the experience, writing, “Thay [sic] advanced on us at dark. The infantry drove them back. All vary tiard [sic].”

During the confused exchanges of fire that flared in the darkness, one southerner was sheltered behind a large post. As a fellow Confederate recalled, “That post showed up from the flash of the guns and the Yankees supposed it to be a man. That trooper said the splinters just showered off that big post at every volley, while he was as flat to the ground as he could get.”

The Attack on Manor’s Hill: “A cold chill runs down our backs”

The next morning, May 15, the battle began with a thunderous artillery duel. Some Federals on the Manor’s Hill line were caught by surprise. “[We] were not looking for trouble that morning,” one recalled.

Confederate Gen. Gabriel Wharton, a VMI graduate, commanded the southern troops that assaulted Manor’s Hill. When he passed away in 1906, he was buried on May 15 – the 42nd anniversary of the battle.

Late that morning, Breckinridge sent his men forward. The Confederates advanced down the slope of Shirley’s Hill and clashed with skirmishers from the 18th Connecticut. One Connecticut soldier said, “we found them too thick and had to fall back.” As they withdrew, the commander of the skirmishers, Captain William Spaulding, was mortally wounded in the abdomen. Carried to the rear, his last words were, “Are they driving us?” Indeed they were, “sweeping like an avalanche” and imperiling the Union position on Manor’s Hill.

Confederate Gen. Gabriel Wharton commanded the southerners who were advancing on Manor’s Hill “like a swarm of bees.” Watching the Confederates advance, their bayonets visible, a Union artilleryman on Manor’s Hill recalled that “A cold chill runs down our backs.” Another said, “it was easy to comprehend what the outcome was going to be.”

Union Major Henry Peale, commander of the 18th Connecticut

Union commander Gen. Franz Sigel arrived on the battlefield about noon. Having established his headquarters at the W.H. Rice house, he rode forward to the battle line. From there, he watched the Confederates deploy and move forward. Col. David Hunter Strother, one of Sigel’s staff officers, said that “The enemy advanced [on the Manor’s Hill position] in excellent order… The front line cheered & rushed to the attack at a run.” The Confederates outflanked both ends of the Manor’s Hill/River Road line, making the position untenable, and Sigel ordered Moor to pull back.

Confederate Assault from Manor’s Hill: “The very air seemed alive with bullets”

Union Col. John E. Wynkoop and his wife Annie. Wynkoop commanded the Union cavalry on the Manor’s Hill line. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

Moor withdrew the 18th Connecticut and 123rd Ohio to a new line around the Rice Farm on the northern edge of town, while the Confederates now positioned themselves on the Manor’s Hill/River Road line. The new Union position was a poor one, in a lane backed by barns and fences, with some men “knee-deep in mud.” The Federals had little time to prepare before the Confederates renewed their attack, advancing off Manor’s Hill. “The Eighteenth Connecticut was hardly in line,” Moor reported, “When the rebels heralded their advance by their peculiar yell, and advanced in two strong lines, by far overlapping our own.” One member of the 123rd Ohio described how, “As [the Confederates] appeared over the eminence we had lately occupied [Manor’s Hill], they poured in upon us such a storm of shot and shell so thick that the very air seemed alive with bullets.” After “a short but resolute struggle” Moor’s line was overwhelmed and forced to fall back in a chaotic withdrawal. “Men of every regiment were mixed up,” recalled one Federal.

The Battle’s Close: “I have never seen such havoc”

Confederate Capt. Charles Woodson’s 1st Missouri Cavalry [dismounted] was at the center of the Confederate line when they manned Manor’s Hill. Woodson’s unit would be decimated later in the battle, officially losing 41 of 62 men. Image courtesy Virginia Museum of the Civil War.

From there, the battle moved north. Despite the confused withdrawal, Moor’s men had resisted long enough to give Sigel time to form a stronger position on Bushong’s Hill. The Federals repulsed the next Confederate attack, only to make a disastrous counterattack of their own. When the Confederates launched a final general assault, the Union line collapsed, and the Federals streamed north. “I have never seen such havoc,” one southern soldier remembered. As night fell, the latest Federal advance in the Valley had once again ended in defeat and frustration.