Marching to the Defense of the Second Battle of Winchester!

I know it’s summer and a time for vacation and relaxation, but we are hard at work here in the Valley. I’m writing because we can forever protect (and open to the public) the location where the Army of Northern Virginia defeated Union Gen. Robert H. Milroy’s defenders at the Second Battle of Winchester – the place where the Confederates kicked down the door to Pennsylvania and cleared the way for the march to GETTYSBURG!

We need to come together RIGHT NOW to raise the $80,000 that we must have to complete this deal. If we get this done, you will have preserved 39 acres that are valued at over $2 million – but are truly priceless as core battlefield… hallowed ground where Lee’s invasion of the North was assured. This is all possible thanks to funding available through the American Battlefield Protection Program and a $1 million donation from the landowner. We only need to raise the $80,000 required to complete the due diligence for the transfer of the property.

What is the “due diligence” required? Well, it’s the completion of the survey, appraisal, and historic assessment; and it’s the legal work and the costs associated with the closing. It adds up quickly, but it is more than worth it. For $80,000, you and I can forever protect over $2 million of battlefield. That means that we are going to multiply the buying power of every dollar that you contribute 25 times!!! Every dollar you send will be worth $25 dollars toward the permanent protection of this amazing piece of property.

When we preserve these 39 acres, we will take 8 highly-desirable industrial building lots off the market and, as part of the deal, we will also secure the permanent trail easement needed to link this property to the Winchester Battlefields Visitor Center! The property is immediately adjacent to the McCann parcels that you helped preserve last year, and, when combined with the neighboring farm protected under easement in 2005, brings into permanent preservation over 242 acres of contiguous property – AND all of it a part of what will be the new Second Winchester Battlefield Park!

So why these acres? What happened here during the battle that makes this the place where the battle was won? And why was the Second Battle of Winchester so important anyway?

Well, as always, take a look at the historic sketch and the map that I’ve sent along with this letter. Even a quick look immediately brings into focus just how critical this property is to preserve. It was here that the three-day battle came to a conclusion, culminating with a Confederate attack on the Federal column that was desperately trying to escape northward on the Valley Pike. In the pre-dawn hours of June 15, 1863, Confederate Gen. Richard Ewell sent Gen. Allegheny Johnson and his troops sweeping around to the east of the Federal positions in Winchester. The goal was for Johnson to work his way behind the Federals, cutting off their escape route and allowing Ewell to capture or destroy Milroy’s entire command.

It was 159 years ago this month that Johnson’s Confederates emerged from the darkness and fog (on the very property that we are attempting to preserve) and leveled a sheet of flame, lead and iron at the retreating and terrified Federal soldiers on the road.

For more than two hours the fighting on this property raged as Milroy’s Union troops attempted to break out of Ewell’s trap. Desperate cavalry and infantry charges surged against the Confederate position on the target property, but, protected by the railroad embankment and supported by artillery, the southern soldiers of the 2nd, 10th and 5th Louisiana Infantry regiments could not be dislodged. In a last-ditch attempt to turn the flank of Johnson’s line, the men of the 67th Pennsylvania pushed eastward along a dirt road toward the railroad embankment and the left flank of the 2nd Louisiana. Seeing the maneuver, the men form the Pelican State turned their line to meet the Pennsylvanians and drive them across the yard and out lots of the Easter farmstead. The Pennsylvanian’s surrendered, as did members of the Federal 6th Maryland regiment who had followed the 67th in their breakout attempt. General Allegheny Johnson himself positioned troops on the 39 acres we now have the opportunity to preserve, and from here he launched the attack that captured, destroyed and disbursed Milroy’s retreating column. Milroy himself was not captured, but hundreds upon hundreds of his soldiers were rounded up as they streamed in all directions. Massive numbers of Union troops surrendered en masse with one large surrender site located on this target property.

When I think about the interpretive opportunity that this purchase creates, it is almost unbelievable. We will be able to open a new battlefield park almost overnight! But if we can’t pull together the $80,000 we need, none of this will come to fruition, the property will be lost and will soon be developed. What’s worse is if this property is developed, it won’t just destroy 39 acres of battlefield; it will severely damage the historic integrity of the surrounding 200+ acres that have already been protected, and end forever the ability to open and interpret this battlefield. We can’t let that happen.

39 acres of core battlefield protected; a new battlefield park opened with the opportunity to have a trail connector to our visitor center and the Third Winchester battlefield park; and all of this while matching your gift 25 to 1!

This is an amazing opportunity, and with a little luck we might be able to have this property preserved and at least the beginnings of the park experience in place ahead of next year’s 160th anniversary of this battle. The Second Battle of Winchester was one of the most complete tactical and strategic victories of the Army of Northern Virginia and arguably that army’s most perfect victory. For General Robert E. Lee, it opened the door for his invasion of the north, which would culminate in his most singular defeat – The Battle of Gettysburg – a little more than two weeks later.

You and I are poised for a massive victory on the same ground, and I am asking you to contribute like you haven’t before to make this happen. $80,000 and victory is ours. We must save this property – and with you in the front line, contributing all you can, we will…

See you at the front,

Keven M. Walker

Chief Executive Officer

To donate to this mission, fill out the form at the bottom of the page

“We knew then that the day was lost.”

– Union Capt. James Stevenson.

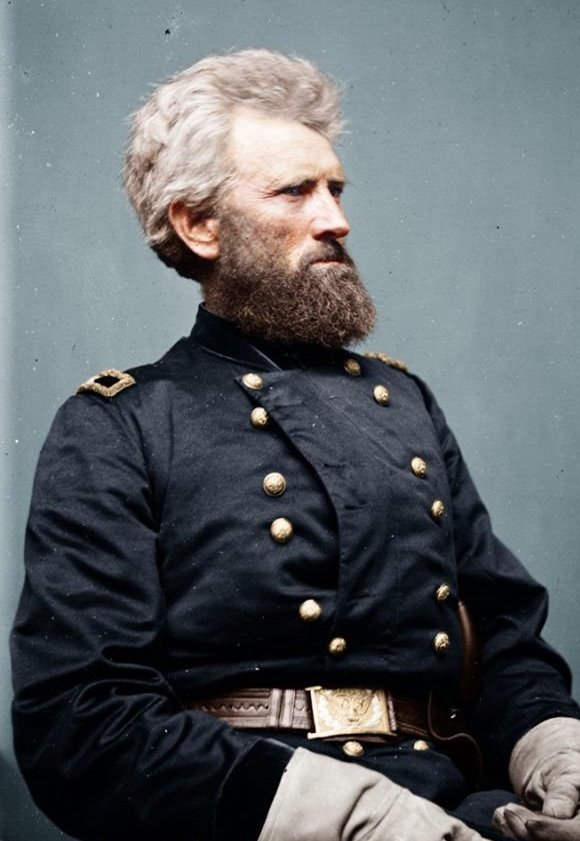

Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell

In June 1863, when Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee launched his second great invasion of the north, he dispatched Gen. Richard Ewell and the II Corps to clear the way in the Shenandoah Valley. On June 13, 1863, Ewell’s columns converged on Winchester’s Union garrison commanded by Gen. Robert H. Milroy. Instead of retreating in the face of superior numbers, Milroy determined to make a stand in the fortifications west and north of town – Star Fort, Fort Milroy, and West Fort – (over)confident in the strength of those defenses. Following two days of fighting south and east of Winchester – and the Confederate capture of West Fort – a sobered Milroy abandoned the other forts and the town in an attempt to “cut [his] way through” to Harper’s Ferry. On the night of June 14, he ordered his men to quietly move out of their defensive positions and head north using the darkness as their cover.

Ewell had anticipated that move, however, and dispatched Confederate Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s division to cut off the Union retreat. Johnson moved east on the Berryville Pike, then turned north and marched his men along the Charlestown Road. The Charlestown Road lead his men toward Stephenson’s Depot and the Valley Pike, directly into the route of Milroy’s retreat. At 3:00 am on June 15, Confederates reached a bridge crossing over the Winchester & Potomac Railroad (on the north edge of the Target Property). Johnson deployed his men to the north as they tried to ascertain the position of the Union forces moving toward them. The 12th Pennsylvania Cavalry made contact with the Confederates near the bridge and fighting began.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson

As the Union infantry moved north on the Valley Pike, Confederate infantry and artillery deployed north of the Charlestown Road and engaged the Union forces. As more Confederate infantry and artillery arrived, the line began to deploy on the south side of the Charlestown Road along the railroad bed (including positions on the Target Property). With their route of retreat blocked, Union forces attempted to break out by attacking the Confederates posted along the railroad bed to their east, including the 2nd Louisiana and 10th Louisiana on the Target Property. (The 10th Louisiana was called “Lee’s Foreign Legion” because they reportedly including men from 21 different countries.) The Confederates captured some 600 Federals, although isolated individuals and small groups escaped. Confederate artillery commanded by Lt. Col. Richard Snowden Andrews positioned near the bridge (on the north end of the Target Property) blocked the Charlestown Road and helped drive back the Union assault.

As the fighting continued, more Union soldiers arrived, including the 18th Connecticut and 87th Pennsylvania moving toward the intersection of the Charlestown Road (northern part of the Target Property). As they arrived, the Louisianans along the railroad cut (on the Target Property) opened fire on their lines. “This was a murderous trap which was not seen in the gray dawn of that fatal morning, and it was first discovered by the flash of rebel rifles,” said 18th Connecticut chaplain Rev. William Walker. Fellow cavalry moving alongside the infantrymen up the Valley Pike took the brunt of the fire and the surprised horsemen created chaos in the infantry lines as they fled.

Sketch from behind the Union battle line near the Target Property during the Second Battle of Winchester

After restoring their lines, the 87th Pennsylvania were ordered forward (towards the Target Property) in an attempt to capture the Confederate cannon near the Charlestown Road. In the darkness, the 87th Pennsylvania moved across Hiatt Run to the Confederate line. Confused by the movement across the field, both the Confederates and the 18th Connecticut began firing at the Pennsylvanians, halting their advance. Milroy himself intervened and stopped the Connecticut soldiers firing. As the Keystone soldiers recovered, they again began to advance but were repulsed by the defending Confederates and retreated.

Milroy then sent the 18th Connecticut and 5th Maryland forward (towards the Target Property) to make a second assault. The 18th Connecticut’s Chaplain Walker said, “The Union forces could see nothing else as they charged into the woods, and up the crossroad, hence the rebels had every advantage, and were not slow to improve it.” The assault again failed. Still determined, Milroy formed the three regiments for another attack, and placed the 116th Ohio and 12th West Virginia in reserve to take advantage of any breakthrough. As the attack went forward toward the railroad cut a Connecticut soldier recalled, “A long line of fire streamed from thousands of rifles, interrupted now and then by the blaze of the battery.” This attack was also thrown back. One Union soldier said, “Our men were fighting like bulldogs [but] they are all cut to pieces.” A shell grazed Milroy’s leg and hit his horse, fracturing the mount’s thigh bone.

Union Gen. Robert H. Milroy

On the Valley Pike, more Union forces arrived. Col. Andrew T. McReynolds’ brigade quickly filed off the Valley Pike onto a dirt road moving toward the Confederate left flank. The 67th Pennsylvania and 6th Maryland moved in column along the road and through the tunnel under the Winchester and Potomac Railroad. The 2nd Louisiana and 10th Louisiana (on the Target Property) changed front to meet the attackers and held off the Federals with the aid of a section of Confederate cannon. Col. McReynolds ordered the 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry to charge (across the Target Property) and drive off the cannon. As the horsemen galloped towards the guns they we were greeted with a torrent of fire. Union Sgt. George W. Nailer of the 13th PA said it “Was the hottest fighting ever done in western VA. The rebels shot rail road iron, from 12 to 20 inches long. I saw horses cut in two by one of the pieces.” The attack was repulsed, and the cavalrymen fled the field, with “only one object in view, and that to escape from the enemy.”

The scene was chaotic. “We saw the teams and artillery horses charging wildly to the rear,” recalled Union Capt. James Stevenson, “And our infantry running in all directions, with the charging enemy close behind them; and we knew then that the day was lost.”

The 67th Pennsylvania and 6th Maryland tried to escape around the Confederate left. Reaching Milburn Road, the 67th Pennsylvania broke ranks at the Jacob Easter farm for rest and water. The Louisiana regiments that had moved from the Target Property surprised the Pennsylvanians, taking nearly 400 prisoners. The 6th Maryland formed south of the road and tried to make a defensive stand, but they were overwhelmed and scattered to avoid capture.

With the Union attacks failing all along the Confederate line, the other Federals began to retreat into the woods west of the Valley Pike. The Confederate line advanced in pursuit. “By this time the fields were all dotted by scattered troops in all direction and the enemy close behind” wrote Sgt. George Blotcher of the 87th Pennsylvania. Gathering in the woods west of the pike, Union soldiers began to wave white flags to surrender. In total, 4,000 men would surrender, half of Milroy’s force.

The defeat and destruction of Milroy’s force cleared the way for Lee’s second invasion of the North, and offered high hopes for the success of that invasion - hopes that would be dashed two weeks later at Gettysburg.